Via FFB's post, I read Chalmers Johnson's piece on Empire v. democracy, Iraq, terror, occupation and the colonial relationship between Iraq and the US. The piece was good, and the quote from Arendt was brilliant:

In her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, the political philosopher Hannah Arendt offered the following summary of British imperialism and its fate:

"On the whole it was a failure because of the dichotomy between the nation-state's legal principles and the methods needed to oppress other people permanently. This failure was neither necessary nor due to ignorance or incompetence. British imperialists knew very well that 'administrative massacres' could keep India in bondage, but they also knew that public opinion at home would not stand for such measures. Imperialism could have been a success if the nation-state had been willing to pay the price, to commit suicide and transform itself into a tyranny. It is one of the glories of Europe, and especially of Great Britain, that she preferred to liquidate the empire."

I was excited. This was well-stated. I would use it in my declonisation lecture to demonstrate the debates that went on in the metropole and the ethics of colonialism for democracies. But, Johnson had only given the book reference--to a book that's 500+ pages long and published often in three separate volumes. Google book it, you say? of course. I did. Unfortunately it's only in snippet view, but I managed to came up with this:

Arendt, Hannah. 1966 [1951]. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

p. 216: ...'"administrative massacres" could keep India within the British Empire, but he knew also how utopian it would be to try to get the support of the hated "English Departments"

all other phrases that seemed like good bets turned up nothing. Seems Johnson quoted Arendt via some sort of bizarre paraphrase. Maybe his notes got mixed up. But that's not cool. It's like putting words into someone else's mouth. What if Arendt meant what she said within a particular context of a specific person she discusses on p. 216, and not more broadly as Chalmers Johnson had implied? Hm.

I google further. Google classic this time. I find about 20 references to Johnson's piece in the blogosphere and then the link to victory.

It's not in Origins of Totalitarianism. Here's the correct citation:

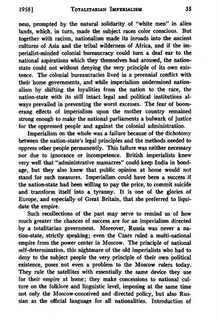

Arendt, Hannah. 1958. 'Totalitarian Imperialism: Reflections on the Hungarian Revolution'. The Journal of Politics vol. 20, no. 1 (February), pp. 5-43. JSTOR link, for those with access.

The quote is on p. 35.

At least Johnson didn't make it up. At least they are, indeed, Arendt's words. I was going to blog about the sacredness of the word--the fact that prose often is chosen as carefully as poetry and one shouldn't just paraphrase and then put those words back in the text as if they are actually there, in that order. Just because it 'sounds about right' for Arendt doesn't mean it's okay to do this.

But now it's just a post about sloppiness. Citing properly is important if people are to follow up on your research--not just to check its vailidity but to read more. To engage in the web of knowledge that supported you to get to this point. That's why links in blog posts are so important and such a crucial part of blogging. It seems, however, that sloppiness is okay now. or perhaps engaging with your source's sources isn't something people do anymore. maybe no one else wanted to see the larger context for Arendt's quote. Wow. now that's sad.

Because maybe it's important to know that Arendt is praising the British in light of the Soviet actions in Hungary in 1956. Her work is, from the little I've read, very historically grounded, and thus this context seems important. But perhaps not. Maybe I'm just being nit-picky. I firmly believe, however, that knowing how knowledge is produced is as important as the knowledge itself.

1 comment:

I'm with you there.

I think it's part of the larger cultural sense that text on-line (or otherwise digitally transmitted) is somehow less serious than printed hard copy text. Because you can make it public so quickly, you should then write it quickly (and carelessly)? Or because it's more easily changed (no more errata slips tumbling out of the bindings of new books), you don't have to worry about getting it right the first time?

I share, in this context, a lovely story about a person of our acquaintance who,upon being called out for sending a hostile e-mail, replied, "[I] hadn’t intended to be rude...e-mails are terrible for tonalities." But there's nothing special about e-mail and tonality, of course: the fact that one is typing and hitting a "send" button rather than a "print" button -- or even typing rather than writing by hand -- doesn't change the language. And to be told by the Poet Laureate of Maryland that he can't control the tone of his written compositions says something pretty damning about either his facility with language or (I prefer to think) the easy acceptance of sloppiness (sloppiness of writing; sloppiness of thinking about the reasons for it) otherwise sane people are willing to make.

But you'll have to pardon my rant -- I'm grading my first essays of the term...

Post a Comment